Listen to article

The current and foreseeable challenges presented by the implications of climate change necessitate swift and effective responses. While exploring appropriate technological remedies is valid, it falls short of a comprehensive solution. The imperative lies in implementing both mitigation and adaptation strategies to facilitate the shift toward a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy. This transition must ensure the preservation of everyone’s future prospects and simultaneously unlock the potential for cultivating novel green economic sectors and business models. By reading this post you will get an understanding of the role of education to achieve a low-carbon and climate resilient future.

Balancing climate action, economic resilience, and social equity

- A stronger recognition of labour rights, which would ease the path to creating more decent jobs.[1]

- The design of proper policy frameworks to back up just transition’s purpose (including policies relative to economic, environmental, social, education and training, and labour issues).

- The explicit inclusion of the gender dimension in policies handling the green transition.

- The integration of all voices—especially those of the most vulnerable groups—in decision-making processes with the aim of achieving a strong social consensus.

Just transition principles must be integrated into education policies for a changing economy

As part of a coherent policy framework, given that the decline of traditional industries and the emergence of greener ones could cause a skills gap, incorporating just transition in education policies ensures that the current and future workforce is prepared with the necessary knowledge and skills to cope with changes in the labour market. Consequently, providing relevant skills for the labour force through formal and non-formal education is essential to reducing skills gaps and achieving a low-carbon and climate-resilient future. Changes in energy production and use, for instance, could lead to the loss of 6 million jobs globally by 2030, whilst creating 24 million new jobs, compared to a business-as-usual pathway.[2] This shift will require people to acquire new competencies.

New roles, reskilling, and upskilling will be necessary for the transition to sustainable economy

Enhancing essential skills development across all climate-affected economic sectors undergoing transformation is imperative and requires a dual approach:

- Innovative schemes led by private companies undergoing the transition. One of these schemes is being implemented by Panama’s automotive industry. Teaming up with the national government and top educational institutions, this sector is preparing energy auditing technicians and charging station installers, while retraining traditional vehicle mechanics to be qualified to maintain electric vehicles (EVs).[4]

- Policies targeting Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) systems. Due to their wider scope, TVET systems are the ones called upon to align formal and non-formal learning programs with the skilled labour demand from different industries.[5]

Should decision- and policymakers anticipate the skills gap that may occur during and after the transition, workers and employees would be better equipped with the right knowledge to cope with changes in the labour market. Conversely, poorly managed education and training systems would limit countries’ ability to deal with the green transition and make it fair.

Governments should leverage existing global green skills studies and make necessary educational reforms to fill the skills gap

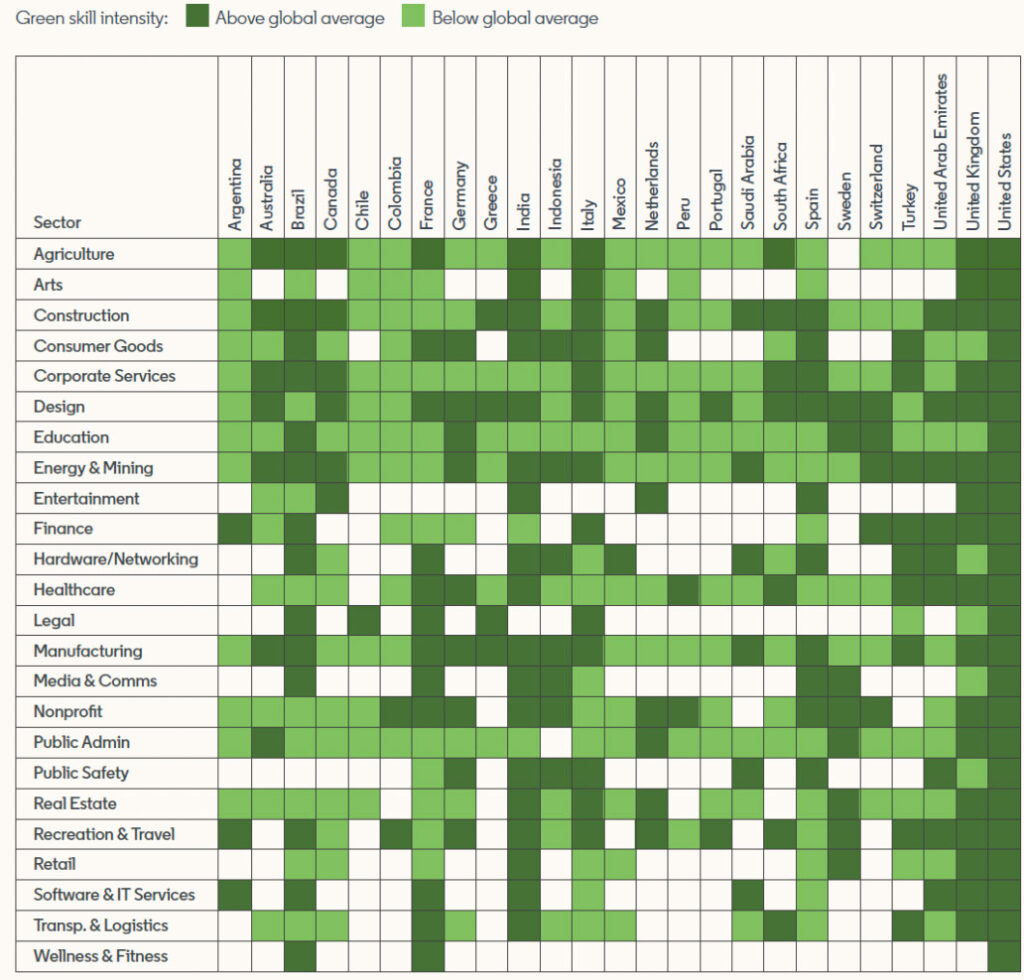

Studies and reports on the development status of green skills worldwide can help government authorities and other relevant stakeholders make informed decisions on the educational reforms that should be implemented to avoid “stranded workers” and provide decent jobs for future workers. According to LinkedIn’s “Global Green Skills Report 2022”, the demand for green talent and green skills is outpacing supply. As illustrated in the chart below, out of the 25 countries assessed, many countries in the Global South are still below the global average when it comes to the development of green skills in selected sectors. This trend indicates that globally, and particularly in the Global South, the gap in green skills development (among other issues regarding education provision) has not been effectively addressed, hindering or delaying the potential to reach a just transition.

5 Steps governments can take to address the green skills mismatch

- Identify the skills needed in sectors of interest, such as energy, agriculture, or waste management, among others. There may be permanent mechanisms or ad hoc assessments to anticipate the education and training demand that would be necessary to satisfy a greener labour market.

- Identify the current education and training supply. Although considered an essential tool to create decent jobs and maintain employment growth in a just transition context, only a small number of countries have put in place proper TVET programs for newly created occupations.

- Design and implement policies to develop and/or strengthen TVET systems. Policies should be put in place to promote the development of new formal education programs and/or apprenticeships or community training to close the gap between the education and training supply and demand previously identified. Uganda, as an example, recently established the Skilling Uganda Task Force, a body aimed at facilitating cooperation between the government and the private sector in identifying training needs and reforming training curricula.

- Development of skills provision programs by the private sector. Besides being involved in the identification of training gaps and the improvement of TVET systems, the private sector might be stimulated to develop the skills it needs. In Guyana, for instance, private companies manage a growing number of industry-aligned training and professional development schools aimed at contributing to the country’s transformation into a green economy.

- Among others, there are two key cross-cutting aspects to consider during the supply/demand gap identification and the policies’ design regarding education for a just transition. First is the proper geographic distribution of the skilled workforce. In the energy realm, for example, a direct link should be established between education and training providers and companies phasing out (e.g., coal-fired power plants) and phasing in (e.g., renewable energy plants), which are located in the same area. In addition, subsidies could be initiated to incentivize local people to choose specific career paths in places where they are most needed. Second are the gender norms and stereotypes that still remain embedded in curricula and teaching. Although women globally outnumber men enrolled in tertiary education programs, female students make up only 35% of the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) area. This gender gap is even wider in the ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) sector, where women make up just 3%.[7]

Skill development, gender equity, and education enhancement will empower the future workforce for a climate-resilient economy

It is undeniable that the path towards a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy will require new, different, and additional skills. Building human capital to power this economic transformation, therefore, will entail a skill development process—which mainly relies on TVET systems—to aid the newly and already experienced workforce in acquiring relevant competencies. In addition, closing persistent gender gaps in education will also help economic sectors thrive on their paths towards sustainability while ensuring a higher percentage of the population achieves better living conditions. Improving education and training systems is another safety net to ensure no one is left behind as countries and societies transition.

[1] ILO defines “decent jobs” as productive work that is performed by both men and women in conditions of freedom, equity, security, and human dignity.

[2] Bray, Rachel, Adolfo Mejía Montero, and Rebecca Ford. 2022. Skills deployment for a ‘just’ net zero energy transition. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 395-410.

[3] ILO. 2019. Skills for a greener future: A global view.

[4] IEA. 2022. Skills Development and Inclusivity for Clean Energy Transitions.

[5] TVET systems are commonly composed of public and private education and training centers, educational and vocational colleges or institutions, and/or formal and non-formal apprenticeship programs.

[6] Bray, Rachel, Adolfo Mejía Montero, and Rebecca Ford. 2022. Skills deployment for a ‘just’ net zero energy transition. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 395-410; ILO. 2019. Skills for a greener future: A global view.

[7] UNWomen. 2022. Leaving no girl behind in education.