Listen to article

Carbon pricing instruments (CPIs) are regarded as an indispensable tool to mitigate climate change as an incentive to encourage changes in production, consumption, and investment patterns towards cleaner alternatives. By placing a price on carbon, governments make fossil fuelintensive activities more costly. This encourages the uptake of cleaner and greener technology through business investments and consumption patterns. Revenues from CPIs can be used towards increasing climate finance, thus further supporting climate action and green development.

The resulting growth in greener industries can give way to a more sustainable economy where people could reap the benefits of decent jobs and the positive health impact of a cleaner environment. The potential for CPIs to overcome existing price barriers to low-carbon development, complemented with effective policy measures, can substantially help countries achieve their climate change and green development goals.

For the purpose of this article, the discussion focuses on how the implementation of CPIs should address risks to consumers, and explains how doing so could benefit CPI implementation. It also acknowledges that country contexts will influence the approach to addressing these socio-economic risks, particularly between countries in the global North and the global South.

Carbon Pricing Instruments

What are the positive impacts of carbon pricing?

- Carbon emission abatements. GHG emission reductions brought on by carbon pricing will bring countries closer to their Paris Agreement goals.

- Redirect innovation. CPIs provide financial incentives to abandon carbon-intensive investments and opt for cleaner, less costly activities.

- Decent job creation. The growth of greener industries can give way to the creation of more decent jobs, offsetting the impact of the phaseout of carbon-intensive industries on the labor market.

- Environmental and health benefits. CPIs incentivize regulated entities to abandon carbon-intensive activities, which have also significantly contributed to local air and water pollution. Phasing out these activities can improve the health of surrounding communities.

Just Transition

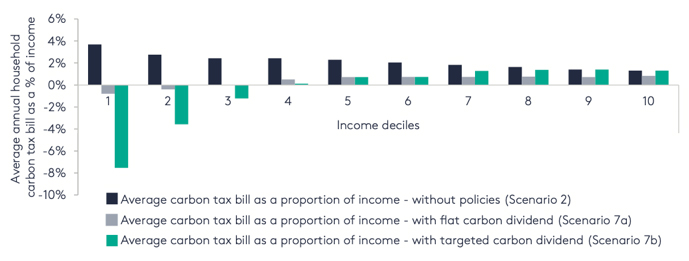

Figure 1. Total carbon tax impact for each decile, split between food, transport, energy and others, for 2030 scenario.

- Housing capital. Those living in more energy-efficient homes will spend much less on energy bills.

- Transport capital. Those with access to more fuelefficient vehicles will spend much less on fuel.

- Geography. Compared with urban and suburban residents, residents in rural areas have a high demand for transport but have fewer alternatives, as public transport tends to be limited. Similarly, rural houses tend to be bigger, more exposed, and require more heating and electricity than urban homes.[8]

Implementing CPIs can therefore disproportionately impact certain communities, and potentially negatively affect their quality of life. Governments should take a just approach toward carrying out climate actions- this will ensure communities are not left behind as a country transitions towardsa low-carbon, climate-resilient economy.

What can just transition do for carbon pricing?

A just transition ensures that all relevant stakeholders equitably benefit from the shift to a low-carbon, climate-resilient economy and minimizes the negative impacts of climate actions. As a result, a just transition can also lead to increased public satisfaction and buy-in, coupled with increased visibility and transparency, prompting further climate action.

Incorporating just transition provides greater transparency on governments’ actions to manage any negative impacts of carbon pricing, garnering public support and preventing social discontent. Failure to incorporate just transition has likely contributed to the public responses to the energy price hikes in various countries:

- The yellow vest protests in France that started in 2018 were partially triggered by rising crude oil and fuel prices. The protests, which lasted almost four years, involved hundreds of thousands taking to the streets, leading to violent clashes and riot police firing rubber bullets and tear gas at protesters.

- Ecuador’s removal of its consumer subsidies on fossil fuels in 2019 led to huge riots that forced the government to flee the capital and reinstate the subsidies 12 days later.

- In 2022, in Kazakhstan, the removal of price caps on LPG led to violent protests in Almaty, which then led to the government restoring vehicle fuel price caps for six months.

What does just transition entail?

Exactly how just transition ought to be implemented has been conceptualized by many entities. One way to unpack the concept is through two types of justice: procedural and distributive justice.

- Procedural justice emphasizes that the dispute resolution process should be fair and that decisions are both made and implemented impartially. When people believe the process to be fair and impartial, and that the rules apply equally to everyone, they are more likely to accept the outcome of the ruling.

- Distributive justice is concerned with the fairness of the distribution of resources. However, the idea of fairness is often different depending on the parties involved, especially when the resource is valued highly.

By upholding these in the execution of climate actions, decision-makers can contribute to ensuring fairness in the process, outcome, and consequences of climate action.

Just Implementation of Carbon Pricing Instruments

What can policies and institutions do?

Because of the widespread socio-economic transformation that a shift to a low-carbon, climate-resilient economy requires, a just transition will entail a strategic, systemic approach that will enable the just transition of individual sectors as climate actions, such as the implementation of CPIs, are carried out. This will involve the participation of many different sectors, government ministries, and key stakeholders.

At the national level, the concept of just transition should be integrated into the country’s regulatory and institutional framework. Policies should recognize the importance of a just transition, while institutions should be created to handle its implementation. For example, a just transition working group could be created to engage players in relevant ministries. Dialogue between ministries can help ensure that actions taken can be synergistic towards a greater just transition implementation. When it comes to CPI implementation, ministries dealing with regulated industries can voice out their concerns and, with other ministries, develop policy responses. Such collaboration should also involve key stakeholders from civil society.

In addition, because carbon pricing instruments ultimately encourage regulated industries to abandon carbonintensive operations and opt for cleaner technology, the government should provide an enabling environment for this uptake to further facilitate the process. Financial incentives should be offered so that companies interested in utilizing cleaner technology can more easily penetrate the market. On the consumer side, since cleaner technology is expected to cost more in the beginning, the government should consider providing financial support through positive indirect carbon pricing signals, such as subsidies towards cleaner energy. This is especially relevant in the electricity sector, where the replacement of heavily subsidized fossil fuel-powered electricity with renewable energy can introduce high electricity prices to consumers. Governments should consider reforms of subsidy schemes to ensure affordable energy prices for their population.

Other national policy-related actions include an assessment of the country’s social protection programs, the development and inclusion of appropriate result indicators, and the assessment of capacity and resource requirements to undertake relevant actions.

Another concern in some developing countries is the availability of fuel sources such as locally-soured firewood, which would not be taxed, and which consumers may opt for if CPIs lead to increased electricity prices. Emissions from the burning of firewood would thus compromise the emission reduction envisioned in the CPI and result in other environmental costs. Government support to alleviate the financial stress that CPIs may cause may be even more crucial in these countries in order to discourage such practices and promote the use of clean energy.

How can just transition be integrated into the design of a CPI?

The design of a carbon pricing instrument should consider both the procedural and distributive justice aspects of a just transition.

When it comes to procedural justice, key stakeholders should be engaged and consulted throughout the design of the CPI. While stakeholders from the government and the private sector are expected, the engagement of the public, which includes consumers, will also be key.

For example, in the period that the Partnership for Market Readiness (PMR) was supporting Indonesia in preparing and designing potential CPIs in the country, various stakeholder engagement consultations were held to engage the public. Seminars and public discussion workshops at the national level involved the general public, which included civil society, non-governmental organizations, and academia.

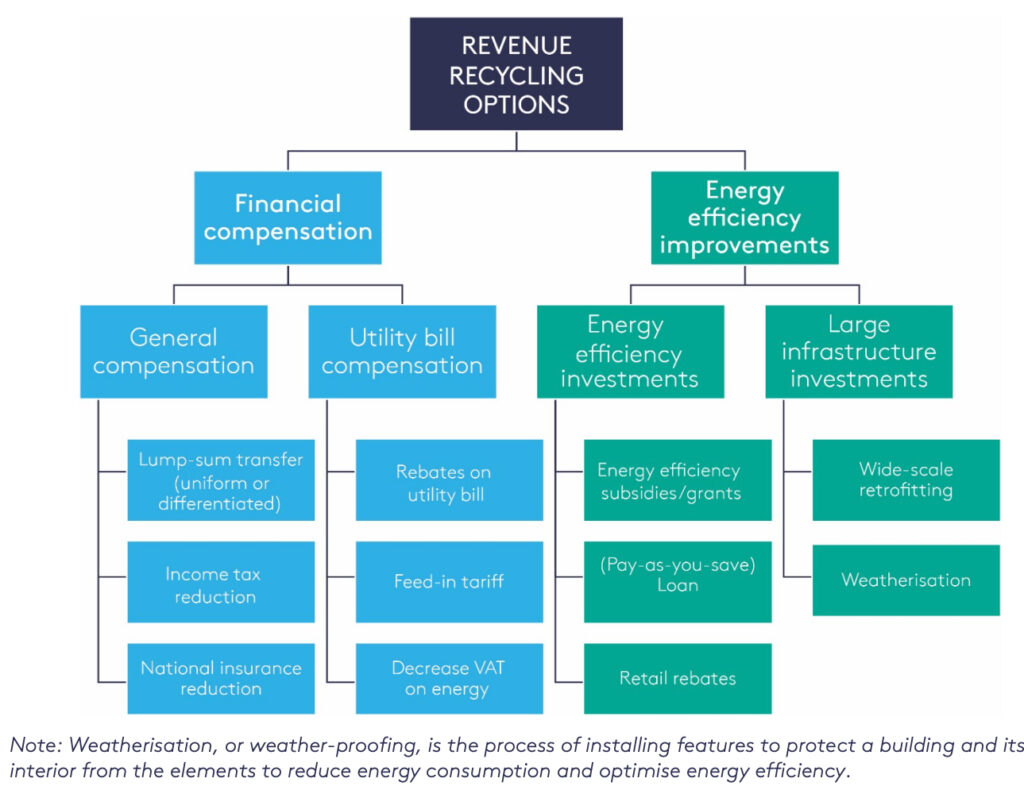

Figure 2: Revenue recycling options within two categories: direct financial compensation and energy efficiency improvements

Figure 3: Distribution of the incidence of a national carbon price with equal per capita transfer for first- and fifth-income quintiles

Case studies also provide positive conclusions about revenue recycling. Table 1 summarizes several policies from three case studies.

In general, studies found positive evidence toward compensating the regressive effect of the carbon tax, in both developing and developed countries, while caveats on the implementation need to be considered in the country context. Overall, the optimal implementation of a revenue recycling mechanism towards a fairer social landscape hinges on the capacity of the policymaker to rebate the revenue to counterbalance the regressive impact potentially caused by CPI implementation.

Conclusion

- Mechanisms like the CPIs will help countries align their low-carbon, climate-resilient strategies towards a cost-effective alternative to abate emissions.

- Besides the climate-related benefits of determining a carbon price or a quantity cap on the level of CO2 emissions, there are social impacts that need to be addressed by policymakers.

- To address social fairness in a CPI implementation, it is necessary to assess heterogeneous distributional effects among geographies, rural-urban locations, and income groups. A transition could not be just if is not counterbalancing existing inequalities and avoiding 7 subsequent gaps to be generated among population groups.

- Revenue recycling mechanisms embed redistributive purposes, while increasing social acceptance of the CPIs policy implementation.

- Among the different alternatives of rebating government revenues, policymakers need to address the impact on the country-specific context, since income groups’ characteristics and individual preferences will vary across countries.

- The CPI analysis/design/implementation should be made with an enduring perspective, aligned to the country long-term strategy.

-

The World Bank Carbon Pricing Dashboard: Map & Data.(Accessed 11 May 2023.).

-

The World Bank 2022 The State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2022.

-

California Air Resources Board. Program Linkage.(Accessed 11 May 2023.).

-

European Commission. Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

-

Nature Sustainability. 2021. Distributional impacts of carbon pricing in developing Asia.

-

Institute for Fiscal Studies. 2021 What is the case for carbon taxes in developing countries?

-

Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. 2020. Distributional impacts of a carbon tax in the UK

-

UNFCCC. 2015. Paris Agreement

-

MDB Group. 2021. MDB Just Transition High-Level Principles.

-

IFS. 2021. What is the case for carbon taxes in developing countries?

-

Partnership for Market Readiness Indonesia. PMR Indonesia Project Implementation Status Report (ISR).

-

Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. 2020. Distributional impacts of a carbon tax in the UK

-

US Federal Reserve. 2021-023. Recycling Carbon Tax Revenue to Maximize Welfare.

Nature Sustainability. 2021. Distributional impacts of carbon pricing in developing Asia.

-

French Association of Environmental and Resources Economists. The equity and efficiency trade-off of carbon tax revenue recycling: a Reexamination.

Resources for the future. Tax Reform and Environmental Policy

Leibniz Information Centre for Economics. 2021. Carbon pricing and revenue recycling: An overview of vertical and horizontal equity effects for Germany