Article 6 cooperation provides potential opportunities for Indonesia, such as mobilizing additional financing for low-carbon development, creating sustainable development benefits beyond emissions reductions, and facilitating technology transfer. Indonesia could capitalize on these benefits by positioning itself in the global market and setting objectives for how Article 6 can support longer-term decarbonization goals in the Indonesian context.

While the focus of Indonesia’s carbon market regulation (21/2022) is on how to ensure NDC achievement, the long-term objective of Indonesia’s participation in international carbon market needs a clearer formulation. It should include a strategy for participation in Article 6 and the use of the VCM not only for achieving the NDC but also contributing to the NZE target.

In the worst case, policy formulation around the NDC targets may jeopardize the NZE achievement. Limiting international cooperation through carbon market activities with corresponding adjustments to after the sectoral NDC target has been achieved will attract finance and technology transfer but will only contribute to the achievement of the NZE target if emissions continue past the duration of the cooperative approach (crediting period).

The main driver should be that any Article 6 cooperation activity that requires corresponding adjustment shall significantly contribute to Indonesia’s domestic mitigation. First, it should be clarified that international transfers under Article 6 and its accounting will impact the achievement of the NDC but not the achievement of long-term emission reduction targets. Second, objectives for Article 6 should include specific priorities for how mitigation activities can contribute to the long-term objectives. Third, to achieve long-term emission reduction targets, activities generating emission reductions through carbon credits need to continue generating emission reductions after the end of the crediting period.

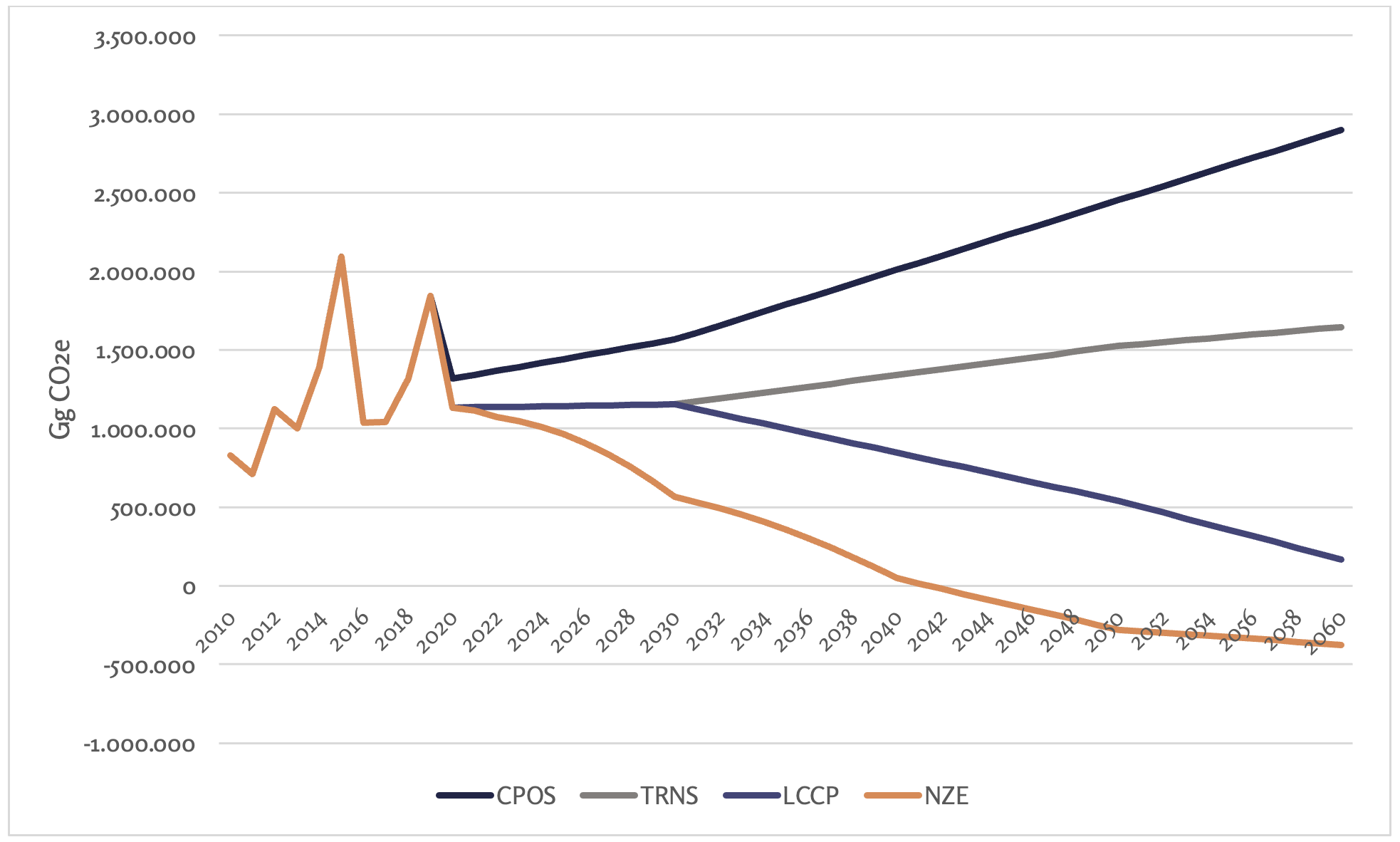

Even in the scenario of Indonesia increasing its unconditional commitments by 37.82% from the current projected level (for the current policy scenario to align with the transition scenario), Neyen’s own modelling estimates that 1,217,723 ktCO2e of emissions reductions are still required to achieve NZE. Policy should broaden the scope of existing regulations to include an approach to international markets that ensures contribution to the NZE target. It should also influence the content of bilateral agreements for Article 6.2 cooperation and may imply strategizing the use of the voluntary carbon markets.

As part of the periodic update of NDCs, countries are expected to increase their level of ambition. In this five-year revision cycle, Indonesia could bridge the gap between the NDC and the NZE to allow for the CPOS scenario curve to align with the NZE. Nevertheless, by doing so and setting unconditional NDC targets that are ambitious and aligned with the net-zero target, Indonesia would most likely struggle to achieve its NDC.

When entering Article 6 cooperation, overselling is the major risk that needs to be managed. With the requirements for corresponding adjustments, Indonesia as the country transferring ITMOs (internationally transferred mitigation outcomes) may have its NDC burden increased by the volume transferred. As a result, Indonesia would be exposed to the risk of not being able to meet its NDC. In such a situation, Indonesia, like every country, has limited mitigation opportunities and the mitigation options have different costs. Indonesia would therefore have to implement more expensive mitigation activities to meet their NDCs because of corresponding adjustments.

This risk is addressed in Regulation 21/2022. The regulation states that overseas carbon trading should not occur at the expense of Indonesia realizing its NDC. This has created a view among stakeholders that Indonesia has a very restrictive policy for international carbon trade. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry has clarified that the policy is that Indonesia is open for international carbon trade.

The following policy recommendations could support this strategy:

The recommendation is to use the LT-LCCR to guide Article 6 participation and not only consider the short-term NDC achievement conditions. If this is done, Indonesian stakeholders as well as carbon credit buyers will know the preferences of Indonesia in terms of technology and mitigation activity types, and they will understand the role of Article 6 in implementing the long-term strategy towards net-zero emissions 2060. Basing the participation objectives on the LT-LCCR means that technology priorities can be explicitly defined. The LT-LCCR should be used to identify technology and financing needs over time in comparison to the current situation in order to identify gaps and explore the co-benefits from mitigation action, as part of prioritizing the country’s strategy to reach net-zero emissions.

Quotas and limitations that can be derived from the LTS-LCCR are not defined. There are buffers set to ensure NDC implementation, but these can be returned to the project developer once the NDC is achieved. To secure NDC implementation, Indonesia could require a larger set-aside of mitigation outcomes to be counted towards its NDC target. Furthermore, ambition can be promoted by ensuring that participation in Article 6 activities contributes to the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement. For example, this could be achieved by limiting crediting periods and setting stringent criteria for crediting period renewal.

Indonesia will have to significantly increase the ambition of future unconditional NDC targets to get closer to the net-zero pathway. To achieve this may require a significant amount of investment, perhaps beyond what it can domestically commit to. In this context Indonesia should be strategic in its participation in the voluntary carbon market (VCM) and should consider the use of the VCM to achieve the unconditional NDC. This translates into not requiring corresponding adjustments for VCM projects. Requiring authorization and corresponding adjustments for VCM activities where this is not required by the independent standard nor the buyer, may seem like an unduly restrictive policy, at least in the short-term. This does not mean that Indonesia should not impose unduly constraining regulations for the VCM in the country. Indonesia has introduced a policy on the VCM for forestry activities based on the wish to “avoid the occurrence of carbon contracts from forests unknown by the government even though carbon exploitation has occurred every year”. Indonesia could have similar requirements for other sectors.

Since the market currently is fragmented, it may benefit Indonesia to be pragmatic, but it needs to be cognizant of risks. In one scenario, Indonesia may lose out on private sector finance flow through the VCM if it applies a strict NDC accounting approach requiring corresponding adjustments in all cases. In another scenario, it may lose the interest of countries that only want to buy ITMOs from countries that have strict NDC accounting approaches. It could therefore be suggested that Indonesia’s policy context should clearly state that any emission reduction that does not include corresponding adjustments will be counted towards the NDC of the host country. With such a signal, the risk of making a specific type of claim will lie with the buyer.

Assuming that unconditional NDC targets are stringent, Indonesia may need to buy ITMOs to achieve the NDC. While this is not something to strive for, if the situation occurs, one issue will be whether the burden should fall on the government or the private sector. Should the Government be responsible for purchases to achieve sector and economy-wide targets, or could purchasing be delegated to the private sector as part of their compliance in carbon pricing schemes such as the domestic ETS. That is, if sector targets in the NDC are ambitious, and these ambitious targets are reflected in the caps for sectors subject to emissions trading schemes (cap-and-trade), then the regulated entities could be provided with the flexibility of using international offsets (ITMOs) in order to stay under their respective caps.

Providing flexibility to entities covered by the ETS is one way of easing acceptance for enlarging the ETS and provides an approach for ensuring the achievement of the NDC if the sectors covered by ETS do not perform as expected. In other words, if these entities cannot comply with their individual caps, they will need to purchase allowances. In a limited market, there may be challenges to liquidity meaning that not all entities will be able to purchase allowances from the domestic market. Under Indonesian regulations, entities can pay a tax when they emit more emissions than prescribed. However, an alternative option is to use imported ITMOs for compliance (compare flexibility of the carbon tax in Singapore). Since these ITMOs can be used towards Indonesia’s NDC, the NDC achievement is ensured despite ETS sectors not performing as expected. Furthermore, the concept of international offsets through ITMOs moves the responsibility of the purchase of ITMOs from the government to entities (companies) in the ETS.

ITMO prices are not transparent as the market is emerging. This may continue to be the case since transactions are between sovereign states or involve companies in bilateral over-the-counter deals. Thus, there is no international market price, nor is there any demand center for ITMOs on which pricing of transactions can be based.

Indonesia may or may not have a direct role in the pricing of ITMOs. UNFCCC rules will not govern the financial flows associated with ITMO transfers and will be up to the contractual agreements of host and buyer countries, as well as any parties they authorize to participate in transactions. Regardless of the contractual arrangements, key factors that could influence the pricing of ITMOs include the following:

Pricing can be an instrument to ensure a sustainable administration of Article 6 in Indonesia and can also be used to set aside financial resources for other purposes, such as implementing additional mitigation activities.