At the COP26 Climate Change conference, countries aim to accomplish the following goals: [1]

- Secure global net zero by mid-century and keep 1.5 degrees within reach

- Adapt to protect communities and natural habitats

- Mobilize finance

- Work together to deliver

Despite the general call for all countries to be involved, not all countries will be participating in the same way. It’s clear that many developed countries will spearhead these efforts. However, it is unclear how lower-income countries will take part in fulfilling these goals and contributing to the wider global initiative to combat climate change.

Determining the difference in roles of countries in climate action will require an examination of their different roles in the precipitation of climate change. As developed countries have largely been the culprit in inducing climate change through their substantial contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), they are expected to take the lead not only because of their technical and financial ability to do so but also because a significant part of the blame is theirs.

But it’s not all about fixing the climate. Countries have also recognized an opportunity to bring about a “global Just Transition,” where climate action is paired with social justice. The welfare of the whole world becomes a priority, with developed countries helping developing countries mobilize to meet their Paris Agreement goals, ensure economic prosperity, and build climate resilience.

This article highlights the differences in the contributions of developed countries and the least developed countries to the cumulative global CO2 emissions and what it could mean for their respective responsibilities in the global effort to fight climate change. Taking this into account, the article then examines the role of lower-income countries in achieving each of the four goals of COP26.

There is a massive disparity among countries’ contributions to global CO2 emissions

Historically, there has been an enormous difference in the GHG emissions of the world’s most and least developed countries. Take the USA for example. Its rapid development during the Industrial Revolution made it the economic powerhouse that it is today. It also resulted in it contributing 25% of the world’s cumulative CO2 emissions since 1751.

On the other hand, Barbados, one of the world’s Small Island Developing States (SIDS), has only contributed 0.0032%.[2]

As global CO2 emissions have been linked to climate change, it is evident that not all countries have had equal involvement in what many have described as the “greatest threat facing humanity.” Yet all countries are still expected to transform their economies to mitigate emissions and ensure a green economy.

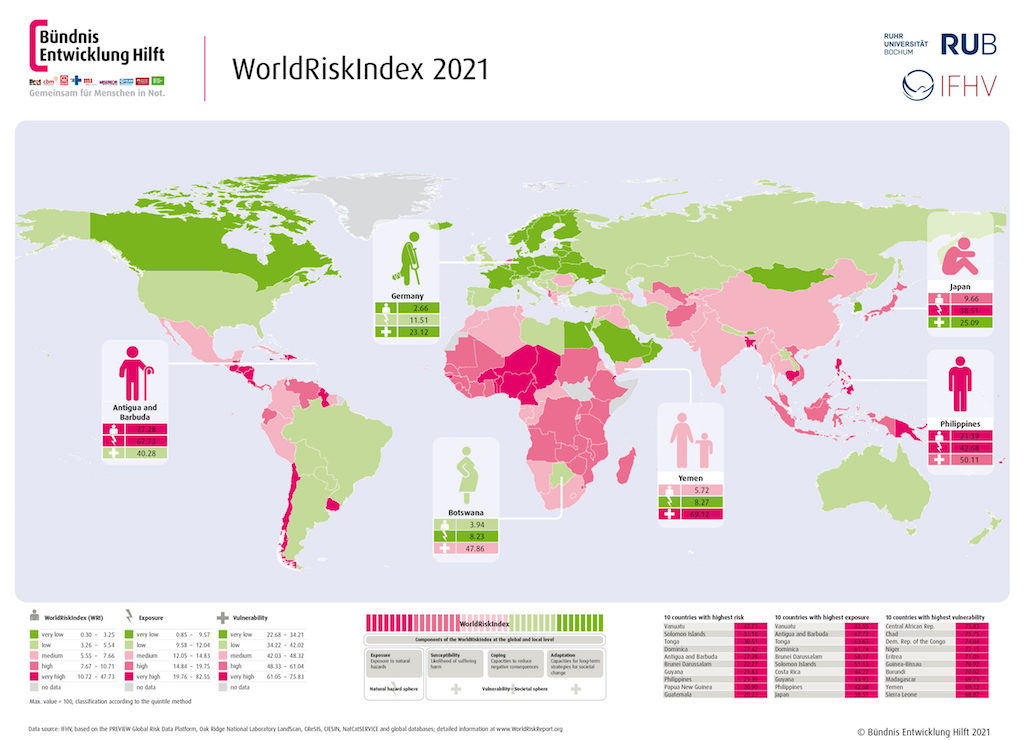

Lower-income countries are most at risk from the impacts of a climate crisis they did not create

Despite having had little to do with the onset of climate change, many lower-income countries are most at-risk when it comes to climate change impact. Whether it’s due to heightened exposure as a result of specific national conditions (e.g. location, size, topography, etc.) or limited financial and technical capacities, lower-income countries may soon find their populations facing hardships due to climate change.

That many lower-income countries remain highly at-risk due to a global calamity that they had little to do with raises the question: Should lower-income nations be held entirely responsible for building their climate resilience through adaptation actions? Or should developed countries abide by the concept of a “global Just Transition” and support these countries to become more climate resilient, essentially as a means of providing reparations?

Sharing the burden of a Just Transition

Despite their small share of the blame, developing countries should still do their part in mitigating GHG emissions and building climate resilience through the adoption of a Paris-aligned development pathway. But developed countries must help. By providing developing nations assistance in their paths to a green economy, developed countries can help ensure not only that the world achieves its Paris Agreement goals but also that the prosperity and economic security that they have enjoyed over the past century—due to the development fueled by the overexploitation of fossil fuels that led to the current climate crisis—is distributed to developing countries.

What do the COP26 goals mean for lower-income countries?

The fact that different countries will have different roles is clear. The Paris Agreement has already recognized the “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities [of each country], in the light of different national circumstances.” Therefore, in the context of the goals set by COP26, it’s important to understand what these responsibilities entail for lower-income countries.

While the lion’s share of responsibility of climate change mitigation lies on developed nations, pursuing a low-carbon pathway can increase climate resilience for developing nations, along with creating economic diversification that leads to greater prosperity.

So let’s explore each goal in detail:

1) Secure global net zero by mid-century and keep 1.5 degrees within reach

Developed countries must lead GHG mitigation

With such negligible contributions to global GHG emissions, lower-income countries are not expected to carry out the brunt of the world’s mitigation effort. In fact, COP26 has recognized the role of developed countries in this endeavor, stating that “it is especially important that developed countries and the largest emitters take the lead.”

But that does not mean that lower-income countries shouldn’t take part. In addition to the call for developed countries to phase out coal power, COP26 urges these same countries to “work together to provide developing countries with better support to deliver clean energy to their citizens.” Indeed, perhaps more imperative than clean energy allowing lower-income nations to reduce their GHG emissions is its potential to improve the quality of life of citizens.

Clean energy can improve quality of life in developing countries

A reduction in the dependence of developing countries on fossil fuels through the adoption of clean energy can have a direct positive impact on quality of life. For example, decreased usage of fossil fuels can mitigate air pollution, which remains one of the biggest hazards to human health in many developing countries. Generated largely through the use of fossil fuels in coal power plants, motor vehicle exhaust, and solid fuel cookstoves, air pollution has been declared to be the cause of 7 million deaths every year.[3] Many lower-income countries in South Asia (e.g., Pakistan, Nepal) and Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Lesotho, Djibouti) rank very low in terms of air quality.[4] A transition to clean energy can help eliminate these health hazards and contribute to a higher quality of life for populations.

Clean energy can also indirectly improve quality of life. Since clean energy sources such as wind and solar are readily available domestically, developing countries that invest in clean energy will rely less on imported fuels and find the resulting energy independence more economically viable. This will make it easier to power essential modern public services such as health care, education, and communications, the poor quality of which has severely impacted the quality of life in many developing countries.[5] Such improvements can uplift communities through better living conditions, which can eventually give way to productive citizens that can contribute to further economic development in the long-term.

Low carbon development can provide economic benefits

Economic development can also be a direct effect of the adoption of clean energy. Investments in renewable energy projects have been shown to have positive impacts on the economy, including job creation. Pursuing a low-carbon development pathway can also provide economic diversification benefits to developing countries. It can lead to increased competitiveness in global markets in green industries, in which sectors such as renewable energy and clean transport are growing substantially, or improved management of natural capital resources whose preservation can increase their value in the country’s economy.

2) Adapt to protect communities and natural habitats

Some countries have greater exposure to the effects of climate change

Just as countries have different levels of culpability in causing climate change, countries also face different levels of impact from the adverse effects of climate change. Although extreme weather events, such as storms, floods, and droughts, all pose a danger to human lives anywhere in the world, some places have greater exposure due to certain factors such as location and topography.

However, the varying exposures different countries may have to climate change-induced disasters do not tell the full story of the overall risk these countries face.

Socioeconomic factors can determine the impact of disasters

A country’s socioeconomic situation can also determine the degree of impact a disaster may have on the welfare of a country’s population. A country that has a low exposure to disasters can still be at risk if it lacks the social, physical, economic, and environmental infrastructures to address the impacts of a disaster. These systems consider public infrastructure, poverty, medical services, ecosystem protection, and investment in health.For example, a developing country such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which relatively does not have a large exposure to disasters, still ranks highly in the list of the world’s at-risk countries due to its lack of coping and adaptive capacities. On the other hand, the Netherlands, which is significantly more exposed to disasters than the DRC, ranks lower due to its existing infrastructure to address disasters.[6]

Such is the predicament of many lower-income countries in the world; many lack the social, physical, economic, and environmental infrastructure to be able to deal with disasters induced by climate change. Coupled with high levels of exposure, these forebode a grim future for many lower-income countries. Since exposure reflects a natural condition that cannot be altered, lower-income countries should focus on building their resilience and the appropriate infrastructures to reduce their risk.

All countries must take measures to increase their resilience to climate change

Certain measures that should be taken by countries everywhere to increase the resilience of their populations include

- increasing gender equality,

- increasing the literacy rate,

- and decreasing poverty.

Furthermore, the Paris Agreement has called for each country to submit an “Adaptation Communication” that “may include information on its priorities, implementation and support needs, plans and actions.” This has also been prioritized by COP26, which considers it as an opportunity for countries to “learn together and share best practice.”

Some adaptations must be country specific

At the same time, some adaptation actions are specific to certain countries. Small Island Developing States (SIDS) around the world, for example, are striving to devise strategies to deal with sea level-rise, including building flood barriers, restoring coastal ecosystems, and relocating facilities and communities to higher ground. Meanwhile, countries at risk for severe droughts, many of which are in Africa, are looking to build infrastructure for aquifer storage, implement saltwater intrusion barriers, and practice water conservation.

Developed countries must provide assistance to increase resilience

Unfortunately, lower-income countries are not in the position to accomplish all that is needed to increase their resilience to climate change.

Developed countries must lend a hand in providing technical assistance to build the capacity to address the myriad of issues developing countries face.

Expertise from developed nations that may be lacking in developing countries can help launch not only the construction of necessary physical and environmental infrastructures for adaptation, but also the development of the necessary societal and economic systems to maintain the countries’ resilience.

3) Mobilize finance

Financial assistance for developing countries is falling short

Tantamount to the provision of technical assistance is the provision of financial assistance to developing countries, in line with the idea of a “global Just Transition.”

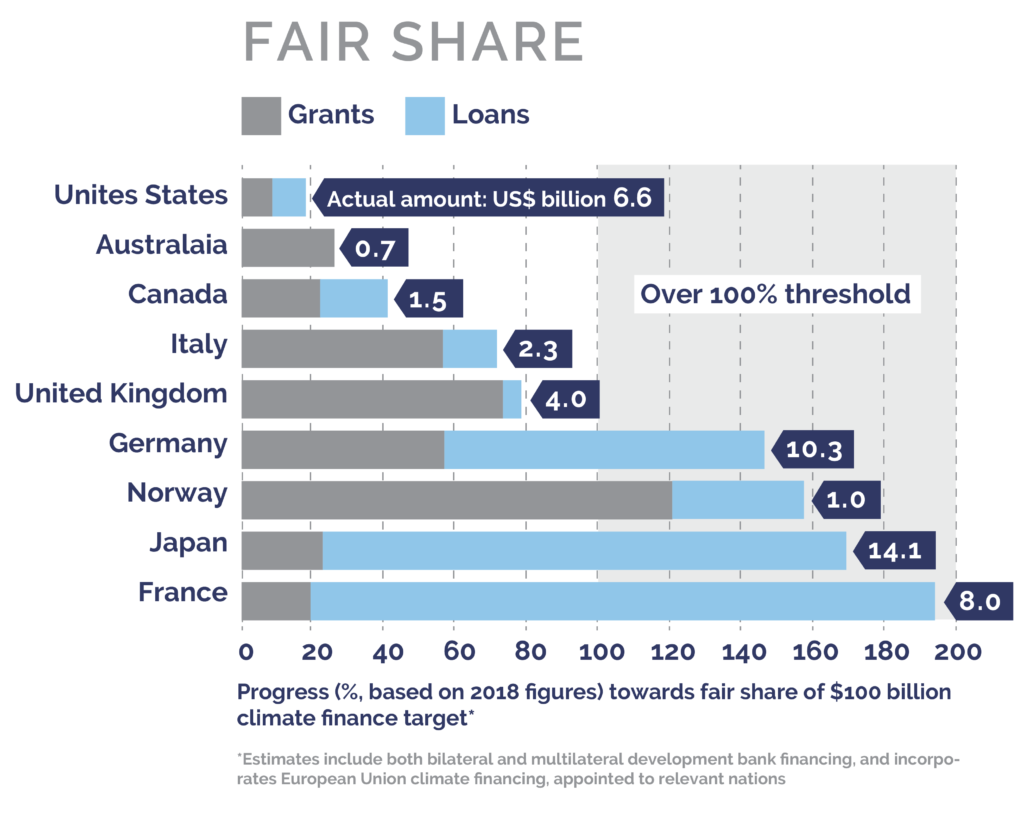

In 2009 at COP15 in Copenhagen, developed countries made a pledge to mobilize $100 billion worth of climate finance every year. However, since then, this figure has never been attained.

The OECD estimates that in 2019, climate financing from developed nations reached only $80 billion. Other estimates argue that the OECD estimates are inflated, saying that only the “benefits accrued from lending at below-market rates should be counted, not the full value of loans.”[7]

Developed countries are underpaying their fair share

Such a deficit makes one wonder, “Who should be paying more?” The World Resources Institute (WRI) has made calculations of the percentage of the $100 billion each developed country should pay—based on account wealth, past emissions, or population—and has revealed that some countries are underpaying their fair share of the pot. Unfortunately, no deals between developed countries have been formally made in terms of the amount to be paid.

Middle-income countries tend to benefit more than lower-income countries

In terms of where this money has been going, some trends have also been discovered. For one, research has found that middle-income countries tend to be the beneficiaries of climate finance, not those with the lowest income. Furthermore, mitigation projects are more favored than adaptation ones. Since a lot of climate finance is given as loans, financers generally look for mitigation efforts that can yield returns. And since adaptation projects typically do not generate money, these tend to be overlooked.

Lower-income countries need finance for adaptation

Certainly, the fact that the poorest, least developed countries are not receiving climate finance is a problem. Developed countries must do more than just provide the money and assume that that’s enough. Some due diligence must be made to ensure that it also reaches those that need it the most, namely those in these lower-income countries.

On top of that, since adaptation is a more challenging issue for many lower-income countries, climate finance in the form of grants should be more concentrated in these efforts. Failure to address the adaptation needs of lower-income countries may leave them stranded in the midst of impending climate change-induced disasters. This can lead to loss of life and sustained damage that may make future recovery very difficult.

Between the failure of developed countries to meet their $100 billion pledge and the skewed delivery of these finances, lower-income countries stand to lose in the fight against climate change if not enough attention is given to ensuring not only that enough money is being granted but also that it is being spent where it should be spent.

In the meantime, while waiting for ample climate finance from developed countries, some developing countries, such as Bangladesh, are trying to mobilize their own domestic climate finance. One way is to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies, on which many developing countries have spent a large amount of their national budgets. Removing fossil fuel subsidies can free funds to be channeled into new green economies or back into society.

But still, developed countries must do more to assist developing countries.

4) Work together to deliver

Lower-income countries need to ensure their voices are heard

As part of this final goal, countries are aiming to finalize the “Paris Rulebook” that was started in 2018 at COP24 in Poland to specify the Agreement’s implementation. Though many parts of the rulebook have been decided on, some parts are still left to be agreed upon, particularly Article 6, which establishes a framework for voluntary cooperative approaches.

International cooperation through both market and non-market mechanisms can provide additional sources of financing for developing countries and enable implementation of NDCs. Therefore, developing countries must ensure their concerns are voiced in order for the rulebook to accommodate their particular challenges and concerns.

If finalizing the Paris Rulebook is achieved at COP26, a new era for international climate agreements will be marked. With the agreement of countries on the implementation of the Paris Agreement upon us, governments, businesses, and civil societies worldwide are now expected to begin revising the ambitious goals they have set and devise innovative ways to meet them. We shall witness transformational changes everywhere, as countries shift to a green economy that promises to sustain the planet, ensure prosperity, and protect the people.

And this includes lower-income countries.

Developed countries must do their part

COP26 is an opportunity for the world’s leaders to reconvene and realign themselves towards meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement. The goals of COP26 can be seen as reaffirmations of the Paris Agreement goals while also serving as reminders of what all countries must do.

In the context of these COP26 goals, lower-income developing countries certainly have their parts to fulfill. They have their responsibility to push for clean energy and introduce a green economy that can bring prosperity to their people. They have their responsibility to push for climate resilience and provide protections that can assure the safety and livelihoods of their people. But they need help.

They now look to developed countries for guidance. As the ones who have emerged as world leaders, developed countries have had the technical and financial ability to push themselves to the forefront of progress. But since this success arose from the exploitation of unsustainable systems that led us to our current climate crisis, they now have the responsibility to use their capacities to assist those that have historically been left behind and are now at risk. Through sufficient climate finance and technical assistance, they can help the rest of the world catch up and protect themselves from the adverse effects of a climate crisis that today’s developing nations had little to do with.

We as a planet are coming up short when it comes to climate action. There is a lot more to do, and developing countries are ready to do their part. But are developed countries?

As the Prime Minister of Barbados Mia Mottley asked at the opening of COP26, “When will leaders lead?”

References

[1] COP26 Explained

[2] Who has contributed most to global CO2 emissions?

[3] 9 out of 10 people worldwide breathe polluted air, but more countries are taking action, WHO

[4] Environmental Performance Index 2020

[5] Renewable energy in developing countries

[7] The broken $100-billion promise of climate finance — and how to fix it